Anatomy of a snapshot

The AOT snapshot itself is quite complex, it is a custom binary format with no documentation. You may be forced to step through the serialization process manually in a debugger to implement a tool that can read the format.

The source files relevant to snapshot generation can be found here:

- Cluster serialization / deserialization

[vm/clustered_snapshot.h](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/clustered_snapshot.h)[vm/clustered_snapshot.cc](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/clustered_snapshot.cc) - ROData serialization

[vm/image_snapshot.h](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/image_snapshot.h)[vm/image_snapshot.cc](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/image_snapshot.cc) - ReadStream / WriteStream

[vm/datastream.h](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/datastream.h) - Object definitions

[vm/object.h](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/object.h) - ClassId enum

[vm/class_id.h](https://github.com/dart-lang/sdk/blob/7340a569caac6431d8698dc3788579b57ffcf0c6/runtime/vm/class_id.h)

It took me about two weeks to implement a command line utility that is capable of parsing a snapshot, giving us complete access to the heap of a compiled app.

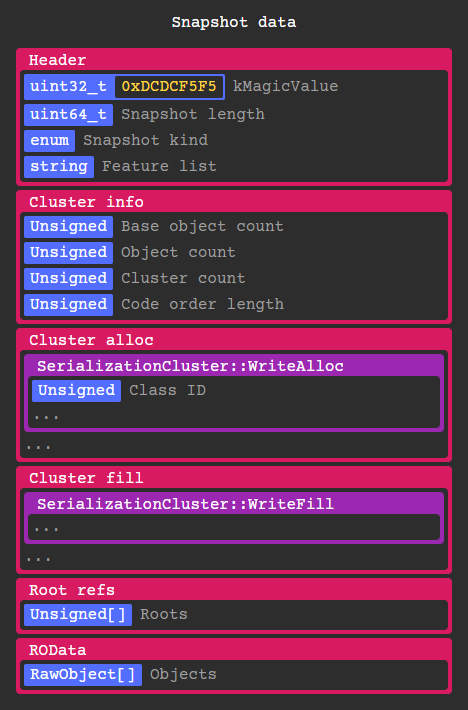

As an overview, here is the layout of clustered snapshot data:

Every RawObject* in the Isolate gets serialized by a corresponding SerializationCluster instance depending on its class id. These objects can contain anything from code, instances, types, primitives, closures, constants, etc. More on that later.

After deserializing the VM isolate snapshot, every object in its heap gets added to the Isolate snapshot object pool allowing them to be referenced in the same context.

Clusters are serialized in three stages: Trace, Alloc, and Fill.

In the trace stage, root objects are added to a queue along with the objects they reference in a breadth first search. At the same time a SerializationCluster instance is created corresponding to each class type.

Root objects are a static set of objects used by the vm in the isolate’s ObjectStore which we will use later to locate libraries and classes. The VM snapshot includes StubCode base objects which are shared between all isolates.

Stubs are basically hand written sections of assembly that dart code calls into, allowing it to communicate safely with the runtime.

After tracing, cluster info is written containing basic information about the clusters, most importantly the number of objects to allocate.

In the alloc stage, each clusters WriteAlloc method is called which writes any information needed to allocate raw objects. Most of the time all this method does is write the class id and number of objects that are part of this cluster.

The objects that are part of each cluster are also assigned an incrementing object id in the order they are allocated, this is used later during the fill stage when resolving object references.

You may have noticed the lack of any indexing and cluster size information, the entire snapshot has to be read fully in order to get any meaningful data out of it. So to actually do any reverse engineering you must either implement deserialization routines for 31+ cluster types (which I have done) or extract information by loading it into a modified runtime (which is difficult to do cross-architecture).

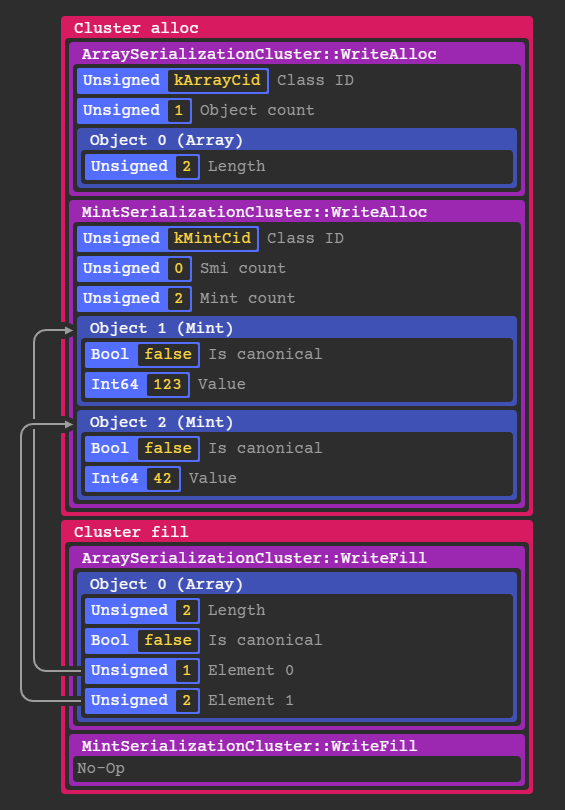

Here is a simplified example of what the structure of the clusters would be for an array [123, 42]:

If an object references another object like an array element, the serializer writes the object id initially assigned during the alloc phase as shown above.

In the case of simple objects like Mints and Smis, they are constructed entirely in the alloc stage because they don’t reference any other objects.

After that the ~107 root refs are written including object ids for core types, libraries, classes, caches, static exceptions and several other miscellaneous objects.

Finally, ROData objects are written which are directly mapped to RawObject*s in-memory to avoid an extra deserialization step.

The most important type of ROData is RawOneByteString which is used for library / class / function names. ROData is also referenced by offset being the only place in the snapshot data where decoding is optional.

Similar to ROData, RawInstruction objects are direct pointers to snapshot data but are stored in the executable instruction symbol rather than main snapshot data.

Here is a dump of serialization clusters that are typically written when compiling an app:

#lint cluster-tbl

idx | cid | ClassId enum | Cluster name

----|-----|---------------------|----------------------------------------

0 | 5 | Class | ClassSerializationCluster

1 | 6 | PatchClass | PatchClassSerializationCluster

2 | 7 | Function | FunctionSerializationCluster

3 | 8 | ClosureData | ClosureDataSerializationCluster

4 | 9 | SignatureData | SignatureDataSerializationCluster

5 | 12 | Field | FieldSerializationCluster

6 | 13 | Script | ScriptSerializationCluster

7 | 14 | Library | LibrarySerializationCluster

8 | 17 | Code | CodeSerializationCluster

9 | 20 | ObjectPool | ObjectPoolSerializationCluster

10 | 21 | PcDescriptors | RODataSerializationCluster

11 | 22 | CodeSourceMap | RODataSerializationCluster

12 | 23 | StackMap | RODataSerializationCluster

13 | 25 | ExceptionHandlers | ExceptionHandlersSerializationCluster

14 | 29 | UnlinkedCall | UnlinkedCallSerializationCluster

15 | 31 | MegamorphicCache | MegamorphicCacheSerializationCluster

16 | 32 | SubtypeTestCache | SubtypeTestCacheSerializationCluster

17 | 36 | UnhandledException | UnhandledExceptionSerializationCluster

18 | 40 | TypeArguments | TypeArgumentsSerializationCluster

19 | 42 | Type | TypeSerializationCluster

20 | 43 | TypeRef | TypeRefSerializationCluster

21 | 44 | TypeParameter | TypeParameterSerializationCluster

22 | 45 | Closure | ClosureSerializationCluster

23 | 49 | Mint | MintSerializationCluster

24 | 50 | Double | DoubleSerializationCluster

25 | 52 | GrowableObjectArray | GrowableObjectArraySerializationCluster

26 | 65 | StackTrace | StackTraceSerializationCluster

27 | 72 | Array | ArraySerializationCluster

28 | 73 | ImmutableArray | ArraySerializationCluster

29 | 75 | OneByteString | RODataSerializationCluster

30 | 95 | TypedDataInt8Array | TypedDataSerializationCluster

31 | 143 | <instance> | InstanceSerializationCluster

...

54 | 463 | <instance> | InstanceSerializationCluster

There are a few more clusters that could potentially be in a snapshot, but these are the only ones I have seen in a Flutter app so far.

In DartVM there are a static set of predefined class IDs defined in the ClassId enum, 142 IDs as of Dart 2.4.0 to be exact. IDs outside of that (or do not have an associated cluster) are written with separate InstanceSerializationClusters.

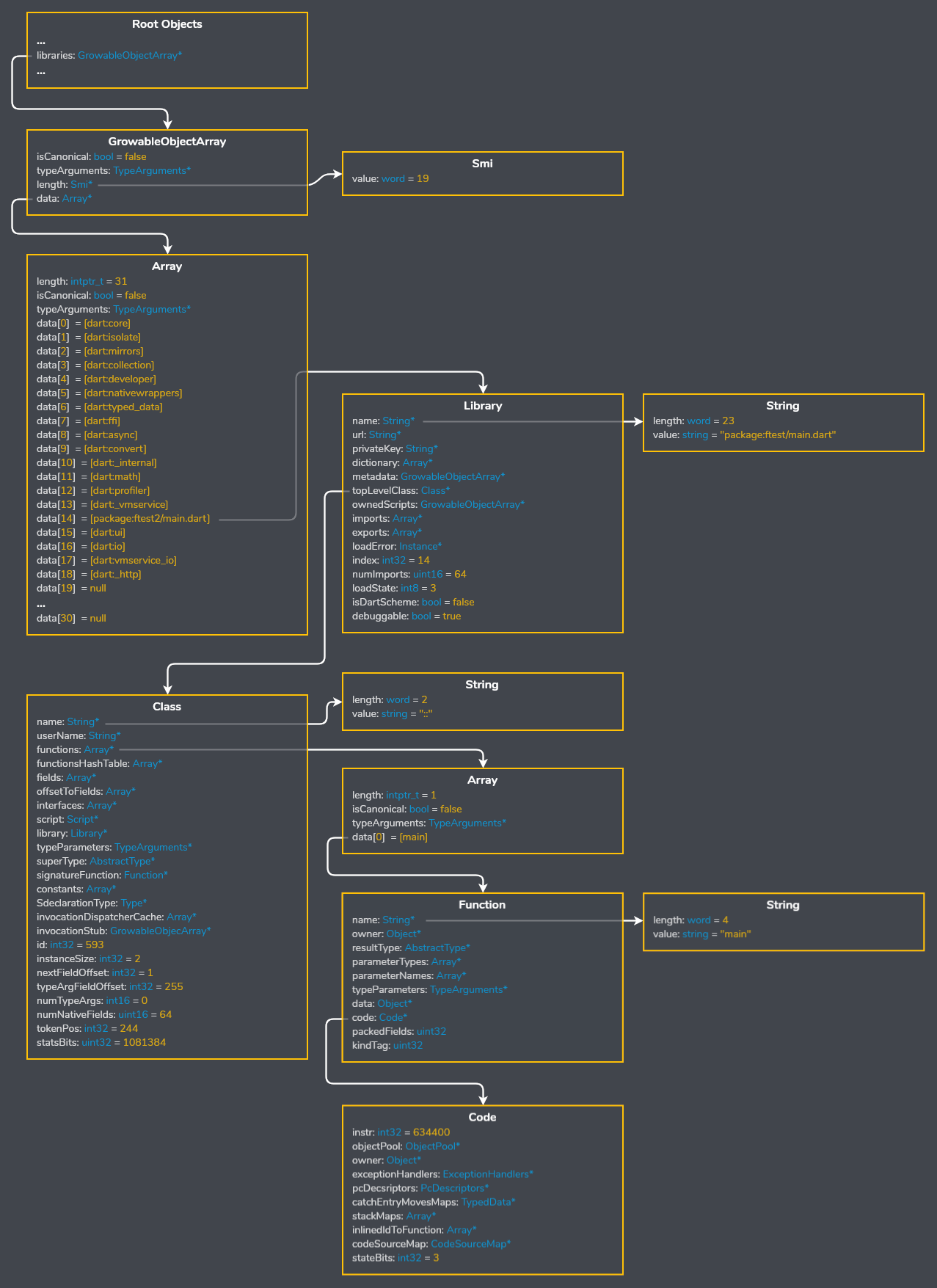

Finally bringing the parser together I can view the structure of the snapshot from the ground up, starting with the libraries list in the root object table.

Using the object tree here’s how you can locate a top level function, in this case package:ftest/main.darts main:  As you can see above the names of libraries, classes, and functions are included in release snapshots.

As you can see above the names of libraries, classes, and functions are included in release snapshots.

Dart can’t really remove them without also obfuscating stack traces, see: https://github.com/flutter/flutter/wiki/Obfuscating-Dart-Code

Obfuscation is probably not worth the effort but this will most likely change in the future and become more streamlined similar to proguard on Android or sourcemaps on the web.

The actual machine code is stored in Instructions objects pointed to by Code objects from an offset to the start of the instruction data.